Australia has set itself a targets-based framework to facilitate by the middle of the century a national transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

It’s a massive ambition costing as much as three entire Australian economies (in current GDP terms) and is the main strategy for mitigating our greenhouse gas emissions.

Reporting to the Energy and Climate Change Ministerial Council (ECMC), the National Energy Transformation Partnership is the framework the Commonwealth, state and territory governments have agreed will guide Australia’s energy system to achieve net zero by 2050 “and deliver the greatest benefits for Australian households, businesses and communities”.

There are many big-ticket items on which members of the ECMC will have to collaborate, from “planning for adequate energy generation and storage” to “accelerating nationally significant transmission projects” to “strengthening energy governance architecture”.

Among the principles that frames the Partnership is the recognition that “broader enablers such as workforce readiness, clean energy supply chains; and community engagement and acceptance will shape the success of the energy transformation”.

Not surprisingly, among the six priority themes for Partnership collaboration there is a focus on “enabler requirements” such as workforce, supply chains, infrastructure and industry development.

A national action plan is supposed to be developed from the assessment focused on investment, supply chain, and community engagement.

It’s an important process that cannot be completed fast enough, because most of the on-ground action in realising the national energy plan will happen outside the metropolitan capitals in the rural countryside of regional Australia – and already it is not happening in the seamlessly coherent way that appears in ECMC announcements.

The Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan, for example, forecasts that regional communities will attract 95 per cent of renewable energy infrastructure investment as well as the vast majority of the 100,000 new jobs, it claims will be created by 2040.

There is no doubt that many regions across eastern Australia are wondering how they might best deal with the energy transition that is planting itself in their paddocks.

Designated Renewable Energy Zones seem to be popping up all over the country leaving many communities alarmed at being press ganged into a process about which they have had little say.

This is a live issue from Tasmania in the south all the way to northern Queensland.

Climate Change Authority CEO Brad Archer acknowledged as much recently when releasing this year’s CCA report, noting: “Communities are also raising concerns about the broader environmental impacts of renewable energy infrastructure in the vicinity of their homes and communities.”[i]

For farmers, the loss of good soil country to electricity generation and transmission infrastructure is a major concern, as is reflected in the National Farmers Federation and its state equivalent bodies taking up the argument for a fairer community involved approach.

Current hot spot – western Victoria

Last month I spent some time in Toowoomba with a visiting group from the Wimmera and Southern Malee region in Victoria.

Coming from a part of Victoria that is a hot spot for renewables investment and transmission infrastructure with no apparent plan from the Victorian Government to leverage benefits for the host communities, this was a group seeking ideas and insights to take back to Victoria.

The visitors comprised a cross-section from local government, regional development, regional media, farming, and community organisations.

They were on a short study tour of the Surat Basin seeking insights that might help them deal with the co-existence issues arising from the rapid influx of renewable energy infrastructure into their region.

We discussed the regional and community development lessons to be learned from the Queensland gas fields experience of a decade ago.

Our visitors were particularly interested in the policies needed to ensure “regional legacy is maximised as land use changes” and how to “collaborate with government to develop a regionally led, long-term shared strategic vision”.

Already home to several large-scale wind and solar projects, western Victoria has been identified by the Victorian Government as a Renewable Energy Zone with high potential for further development.

Further complicating the local outlook are proposed rare earth mining ventures on good cropping country that will completely contradict the history, heritage and landscape of a number of farms in the Wimmera.

Proponents argue that the transmission infrastructure already slated for construction will bring more than $6 billion in investment to western Victoria with close to 2,000 jobs and a further 3,000 indirect jobs in the flow-on.

Regional leaders acknowledge that their communities are “facing real challenges” in responding to the inwards rush of renewables and related transmission infrastructure.

Western Victoria is a traditional farming region comprised largely of broad acre wheat, barley and canola farming with local service industries in the towns.

Like a lot of other rural communities, it is characterised by an ageing population, limited economic diversity, and a slow drift away of young people seeking opportunities elsewhere.

Reports suggest there is a conflicted mix of emotions and perspectives afoot in the communities, ranging from the excitement at the prospect of new infrastructure, jobs and investment to entrenched rejection of the very notion of renewable energy and its role in the energy transition.

The frustration and worry by many landholders is undeniable and understandable, given the region’s history in agriculture.

Community feedback suggests the early engagement strategies of the renewables sector and the related electricity transmission sector have not been very effective.

Quite a number of landholders feel powerless in the face of government backed industry development.

The payment of negotiated royalties (or compensatory payments) to some landholders around wind farms, solar energy, and transmission lines is generating talk of “winners and losers”.

Further community division and alienation is a likely portent if an alternative approach is not put in place very soon.

Understandably, leaders in the change zones of regional Australia will be interested in knowing more about the collaborations and partnerships with State and Federal Governments which have delivered the greatest results for regional communities.

Sabiene Heindl from the energy industry’s ESG initiative, The Energy Charter, acknowledges that the impacts of renewable energy infrastructure “are real and diverse on landholders and regional communities, including visual impacts, financial loss, biosecurity risks and biodiversity”.

She says that “Landholders and communities identify limited benefits from energy transition infrastructure” and that a “focus on impact mitigation is required to facilitate co-existence” between the existing agriculture sector and the new arrivals.

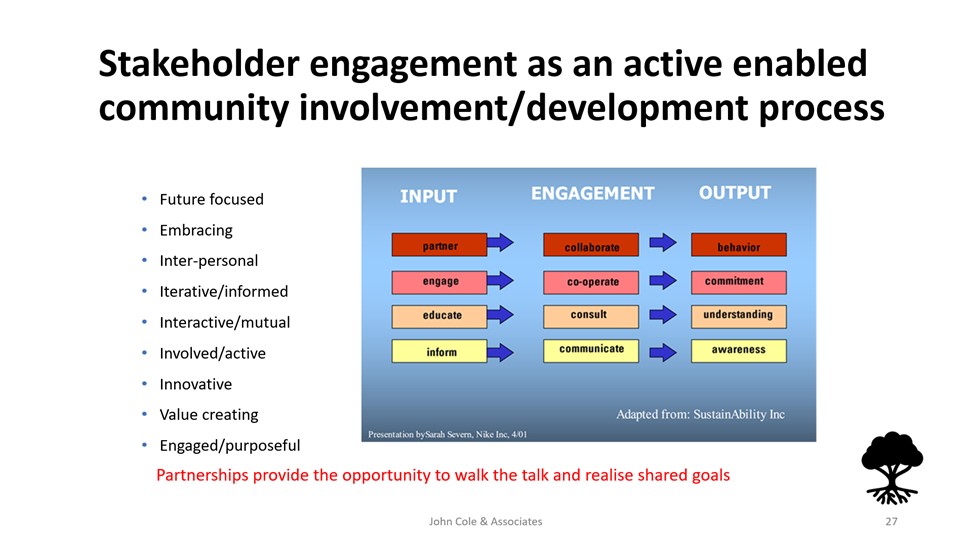

The Energy Charter has authored a “Better Practice Social Licence Guideline” for the energy industry and Heindl advises that “Strong engagement and delivering genuine shared benefits with landholders and communities is critical to realising the opportunities”.

Her assessment is correct.

This is a message which 15 years ago, had it been implemented then, might well have seen very different regional development outcomes flowing from Queensland’s coal seam gas industry.

Are there lessons from Queensland’s “gas boom”?

In what was ‘a rush to gas,’ four multinational consortia launched an ambitious program to install a vast network of wells and pipelines across the Surat Basin, a region the size of Germany, while simultaneously building three LNG plants in Gladstone.

It was a government sanctioned, some might say government commissioned, race for export profits and royalties involving some of the biggest global players in the oil and gas sector.

The Queensland Government took a hands-off approach in part because the industry players were very large and able to express an appetite for risk that would not have been prudential had they been smaller companies – like those that populate the renewables space today.

Driven by an investment of close to $70 billion from the time the roll out of extraction infrastructure on farming land began in earnest around 2008-09, the aim was to have LNG exported from Gladstone before the end of 2015.

That goal was achieved – but along the way in a venture of such scale and accomplishment, there were mistakes, and they were made not just by industry.

The Queensland Government also made its fair share, being largely unprepared for what was to transpire in the Surat Basin as landholders and communities awoke to the scale of impact and dislocation that was to follow.

Communities and landholders too were also overwhelmed by the scale and pace of company activity as land access was secured and the construction phase began.

Key messages for regional Australia inspired by the CSG experience

- Get on the front foot and organise constructively

Reflecting on the Queensland experience my first message to our Victorian visitors was to be involved and organised from the farm to the regional level as soon as possible.

Establish your own governance mechanisms, platforms for consultation and cooperation and think outside the normal structures.

Rather than jump into the trenches and put up the barricades, organise to engage effectively and constructively, the aim being to make change work for your region.

Don’t wait for government to save you or frame a strategy for the region because likely they won’t.

In fact, in the absence of a workable Land Access Code and regulatory framework which evolved as the construction boom got underway, the initial path in Queensland was one of constructed conflict, later requiring mediation and occasional court arbitration between gas companies and farming landholders.

If the mistakes of the past are not to be repeated, it means local government and regional development organisations not shillyshallying around but getting on the front foot and leading regionally with a clear message to other levels of government and industry.

Also don’t be distracted by the efforts of activists and others from outside seeking to stage their protest agenda using your region or community as a platform.

2. Adaptive governance is better than co-existence

The word commonly used to describe the desired outcome in resolving conflict between agriculture and resources and energy industries is “co-existence”.

It means living or existing together, peacefully possibly, but not necessarily without conflict so long as it is managed.

As an organising concept in regional development, “co-existence” has major flaws and sells short the possibilities that might be achieved regionally if existing and new industries work together collaboratively with the involvement of local government and stakeholder communities.

In a regional setting, the ‘together but separate and apart’ implications of “co-existence” flies in the face of the meaning of “community” which is interdependence, integration, shared interest, and mutuality of interest.

Co-existence as an engagement goal also reflects a top-down approach to regional development with governments and industries dictating to communities what will be good from them and imposing it irrespective of local wishes.

The term fits well historically with the imposition of mining and gas wells on farming communities, but the development of renewables sector and the great re-wiring of our electricity system could be more ambitious when it comes to on ground realities.

A far better alternative is an active ground up approach which requires its own adaptive governance [ii]umbrella and which involves regional communities thinking as organisations and acting as co-initiators and co-sponsors of new industry developments that will help diversify and develop their economies.

Adaptive governance simply explained is an organised polycentric process to deal with rapid change at various levels from enterprise to region.

It may draw on and include a diverse range of interests and sources of authority.

Quite purposefully adaptive governance models extend beyond normal and formal traditional structures (like three levels of government or private vs public sector) to emphasise a role for collective actions, experimentation, participation by all parties related to the issue, and shared responsibility and shared knowledge by all relevant stakeholders[iii].

A system of adaptive governance functions at different levels of complexity and composition and is flexible and not owned or controlled exclusively by any one of the stakeholders involved.

It is dynamic and will change in ambit accommodating more than one goal, in fact in a regional system it will embrace a diversity of goals across economic, social, cultural and ecological acknowledging they are all inter-connected.

Adaptive governance in a regional development context is the opposite of ‘moment in time’ top-down prescribed development.

A good example of regional development thinking created in an adaptive framework is the proposed RAPAD Power Grid in outback Queensland.

This is the proposal by the Remote Area Planning and Development Board of Central Western Queensland with its seven local government members to link up with VisIR (formerly CopperString 2 now known as CopperString 2032) to promote a 5.2GW transmission link between Hughenden and Biloela.

RAPAD probably does not think of itself as an adaptive governance platform, being a collaboration of local authorities established to mobilise and maximise the utility and reach of scare regional resources.

It’s aim is to leveraging investment from government and the private sector in projects as diverse as roads, communications, training, energy and enterprise development.

In parts of Australia best suited for the formatting of a renewables industry linked to major clusters of renewables generation and industrial consumption, the RAPAD Grid project makes great sense and seems to invoke little community concern because it fits with the visioning and planning work done across the region for the better part of a decade.

In other words, it is well-socialised locally.

One of the great things about the RAPAD Power Grid is that it will facilitate clusters of new industries in places like Barcaldine, because the emphasis is also on creating industrial users of clean energy in the regions – not just funneling it all into the eastern connector.

This point should be emphasised because while the current national renewables strategy is heavily centralised and aimed at the major Eastern network, the dis-aggregated, decentralised nature of renewables generation should be leveraged to deliver industry development and economic development opportunities for host regions.

The RAPAD Grid is a real regionally generated development proposal whose process is worth picking up on or at least learning from by other regions.

Another adaptive initiative from Queensland worth studying by regions looking to set up their own facilitative platforms came about because of the coal seam gas boom.

Toowoomba Surat Basin Enterprise was launched in 2011.

With Toowoomba Regional Council as its main shareholder and member is a good example of local initiative in grabbing a leadership and brokering position in regional development.

TSBE took the initiative with backing from Toowoomba’s Wagner family, the Toowoomba and Western Downs Regional Councils, and local institutions like the University of Southern Queensland as well as local contractors, developers, and financial institutions.

For more than a decade, as a major member-based advocate for the region, it has focused on leveraging regional benefits from the transient coal seam gas investment while also linking the region’s agricultural and major services sectors into new business opportunities.

TSBE has performed best as a business and investment brokerage and advocate for new projects and provided a powerful and persuasive adjunct to local and state governments in pushing for major infrastructure like the Toowoomba by-pass.

It provides a useful model to be adapted, possibly extended, and adopted by other regions dealing with rapid change.

3. Look beyond all the hype

There is a lot of hype associated with major infrastructure or investment projects, economic benefits are inflated, short term upside is conflated with the longer term, and unrealistic claims – positive and negative – are bandied about by all sides.

The political message tends to oversimplify the process suggesting that all good will flow from the projects and naturally trickle down into stronger more resilient communities.

The result of that tends to workforce dislocation as skilled workers are picked up by the higher remuneration of the investing projects.

It also leads to what some have called “beads and trinkets” virtue signalling by the investing industry delivering on ‘feel good’ community items like upgraded sports grounds facilities and maybe a coat of paint on a community hall or a couple of university bursaries for the local high school.

Being able to look beyond the hype and clamour is vital for a region if it is to organise and mobilise all that is needed to engage effectively with the investing industry.

That means looking beyond social offsets and focusing on strategies and projects that will strengthen the region’s economic capacity through new housing, employment attraction and retention, skilling and training of locals and newcomers, and supply side procurement supporting regional enterprise and newcomers.

Enabling public infrastructure like roads, bridges and communications should not be off the agenda.

In the Surat Basin, the gas companies were major funders of everything from airport upgrades and expansions to sealing rural roads, albeit roads they were using too and airports through which their workforce largely flew in and out of as FIFO workers.

4. Communication must be transparent and inclusive

A crucial factor is effective communication between the main players, and besides keeping a cool head, this requires transparency, accuracy, relevance, and integrity in the flow of information.

During the initial phase, the Queensland example was characterised by multiple asymmetric and inadequate information flows of information which meant that no one party at any time had the full picture of what was happening to inform a regional strategy – even if they had one. (See diagram).

Even as late as 2019, an independent analysis by the Queensland Audit Office found that government agencies were still contributing sub-optimally by working in silos and failing to coordinate their planning, information, and data-sharing[iii].

It’s too late when things have settled down five years down the track to be trying to leverage strategically significant outcomes from the recently arrived energy sector.

Experience tells us that the new industry will have little background or experience dealing with the intended host region, so it will be a learning experience all round.

It means all relevant regional stakeholders being involved in a structured conversation that starts with an emphasis on information sharing and mutual education and works toward aims to a shared view for the region’s future as is possible by adapting to and accommodating the interests of the various parties at the table.

Call it an adaptive governance strategy which has flexibility and diversity in its critical composition, including social and cultural as well as economic/business and governmental clusters.

5. Trust requires patience, respect, and performance

Good regional development is really good regional adaptation, so the community vision must be more than a view from the trenches sketched by the alienated.

There is little point coming to a discussion or negotiation mindfully determined to ignore opportunities or do little beyond dig oneself further into a hole.

And there is nothing to be gained for new industries arrogantly presuming that they will prevail one way or the other – humility, respect, and a willingness to learn from the locals are useful attributes for newcomers if they are to secure engagement and support from the regional stakeholders.

CSIRO’s Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance put it aptly in a 2013 report when they wrote:

“As originally conceived, the notion of a social licence to operate reflects the idea that society is able to grant or withhold support for a company and its operations; with the extent of support being dependent on how well a company meets societal expectations of its behaviour and impacts.

A social licence is tacit, intangible and context specific. It needs to be earned and is dynamic as people’s experiences and perceptions of an operation shift over time”[iv].

The most important ingredient in building trust with rural and regional communities is to be “real” – honest and transparent and respectful of people, culture, and country.

Far more can be achieved in collaboration with regional communities when the mentality of corporations and government moves beyond the notion of offsetting investment in soft community infrastructure to genuine engagement, collaboration, and partnership.

6. Create time and space for innovation, collaboration, stakeholder learning

To be achievable, an ‘adaptive regional vision’ should set the playing field boundary within which the parties will work out how they will adapt together – that is, learn on the run, learn off each other and together, deal with new knowledge, develop new and different types of relationships, adjust the game plan to changing expectations, and assimilate the change on planned and agreed terms rather than haphazardly.

Essentially what is being created in this process is a new regional system – natural, social and economic – in which they key players and stakeholders trust each other.

Resilient communities do not fight against change, rather they position themselves to leverage as much long-term benefits as possible from the rush of investment that flows from something as big as the low carbon energy transition.

Most of all, it means locals taking a good share of the responsibility for the regional future and engaging positively and powerfully with state and federal governments.

For our metro-centrist governments, regional development is not a lived experience, but rather part of a broader strategy that sees the regions as a resource to be exploited for broader state or national benefit.

Savvy regional communities know from the start that no one else is better invested to speak for them and their future.

7. Government can help by taking a longer-term approach

That said, if there are lessons from Queensland and there are, it starts with government being more proactive and constructive in setting the performance expectations it has for the investing industry as it engages with regional communities.

Regrettably, the Queensland government spent the better part of the decade trying to work out a value adding role for itself – beyond the core regulatory stuff around health and environment – and even then, the distrust generated in the early days was not wholly mitigated.

So rather than have a rush to riches in the rollout of new projects, it would be far better for government to require the energy industry to work pre-competitively, to sit down and engage with communities and drive a constructive conversation about how it might integrate and involve itself long term end in delivering sustainable outcomes and benefits for the region.

This is a point to emphasise because the ‘major projects’ conditioning process used by the Queensland Government generated much of the subsequent haste and inefficiency that impacted regional stakeholders in the infrastructure roll-out.

The big gas companies were asked to jump through a lot of hoops to provide performance assurances that could not be guaranteed but looked good in parliamentary speeches and provided scope for blame shifting if something went wrong.

The State government should have ‘walked and chewed gum at the same time” by regulating and playing a partnership role with the industry and the regions in rolling out an adaptive regional development vision.

A constructive, creative, and collaborative project-conditioning regime in which risks are acknowledged and shared rather than ‘hype-washed’ is more likely to generate community benefit in the region.

It’s the kind of thinking Queensland Governments used back in the 1960s and 1970s facilitating especially the development of the metallurgical coal industry in central Queensland where new towns were established, and rail and port infrastructure built.

This does not mean suppressing free enterprise and the innovation and impetus to be achieved from private sector competition, rather it means identifying those areas where efficiencies can be achieved through industry collaboration for their benefit and others.

A good topical example would be avoiding unnecessary duplication of transmission or gas line infrastructure.

Most of the lessons learned in Queensland by both industry government and the communities happened long after the coal seam gas ‘boom’ was underway.

Not enough attention was devoted to develop a coordinated strategy to manage local impacts on workforce, housing infrastructure, and roads and indeed there was an expectation that the gas industry, big as it was, could pay for everything.

Government should understand its most useful role is to paint the boundaries of the “playing field” with strong legislative and regulatory lines – setting the preferred direction and stating the non-negotiable – leaving the innovation that comes from commercially focused business and empowered communities find its place and shape.

8. Accountability agencies must earn trust of all stakeholders

Recently, the Queensland Government extended the remit of the GasFields Commission to “promote coexistence of renewable energy developments, resources, agriculture and other industries and provide support for communities with a trusted, independent body for information, education and engagement”.

Billed as part of a broader program “to ensure energy providers work closely with councils and local communities to ensure locals benefit as part of the energy transition”, the GFC upgrade is supposed to “facilitate local partnerships and empower regions”.[v]

The Queensland GasFields Commission came into being in 2013, as an initiative of the Campbell Newman LNP Government, to “manage and improve the sustainable coexistence of landholders, regional communities and the onshore gas industry in Queensland”.

Three years later it was still learning when an independent review highlighted shortcomings “communications with stakeholders” and a lack of rigour in the “collection, analysis and reporting of data”.

The independent review in 2016 evidenced poor performance by the GFC in “some of its statutory functions” and “strategic and operational planning and reporting”.

It essentially concluded that if there was to be an umpire or mediator appointed by government, it had to earn the trust of all the stakeholders, not just some of them.

It recommended that to achieve this the Commission should:

- facilitate and maintain a harmonious and balanced relationship between landholders, regional communities and the onshore gas industry in Queensland.

- proactively monitor and publish comprehensive data about formal interactions between landholders, CSG companies, government agencies and dispute resolution bodies.

- proactively collect and publish data so the growth of the onshore gas industry in Queensland and the properties impacted can be better understood.

- develop an extension and communication program to help landholders to become more informed and self-reliant in relation to their legal rights, the management of their land when subject to CSG activities and the developments in science and leading practice relating to the onshore gas industry.

- be the trusted advisor to government and stakeholder representative bodies on strategic issues including the status of the coexistence model.

This is a pretty good list of support functions that would help stakeholders in an adaptive governance framework for regional development – so long as the relevant government agencies work with the GFC on an agreed approach.

That was not the case as recently as 2020 when the Queensland Audit Office found that:

“The regulators could enhance their current regulatory practices by better coordinating their planning, information, and data sharing. Work units within and across the regulators use different systems to support their work. The lack of system interoperability (when systems can exchange data and interpret that shared data) makes it difficult for the regulators to collectively coordinate and report on regulatory activities[vi].”

The upshot was continuing distrust by some stakeholders in the efficacy and integrity of the regulatory process in holding industry transparently to account – a decade on from the start of the Surat Basin investment.

A few years further on and it is fair to say that the GasFields Commission is performing much more effectively, having learned from its own experience in a changing operating environment that is still not without its ‘unexpected issues’.

That said, there is through the GFC, a range of outputs that emphasise evidence-based decision-making, cater to the provision and use of robust science and data, generate information and education for stakeholders about each other and the shared context in which they operate, deliver access to disputes resolution mechanisms, and informs a regulatory framework that defines the non-negotiable.

9. Incoming industries evolve in time and place too

Most stakeholders would also acknowledge that the onshore gas industry has learned and adapted along the way too, especially in its technical performance, especially in minimizing landscape impacts of gas well construction and operation.

An expert analysis of the industry in Queensland essentially confirmed that the big gas projects really only achieved commerciality by “improved drilling and completion technologies to achieve commercial rates of gas production”[vii].

Stakeholder engagement by the major onshore gas companies these days is much more nuanced and respectful compared to the ‘wild west’ days of a decade or more ago.

The takeaway from all this for regions is that the investing industry of today in ten- or twenty-years will be most likely a very different industry, such is the pace of technological development in science and engineering – and the changing practice of earning a social licence to operate.

10. Learn from the past, do your own research

One of the most positive things about the Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan which was released back in September 2022 is the emphasises it places on “partnering with communities to realise the benefits and opportunities created by the energy transformation”.

The Queensland Government has committed $19 billion over the next four years to start towards a $60 billion aim of achieving targets of 50 per cent renewable energy by 2030, 70 per cent by 2032, and 80 per cent by 2035.

The Queensland Government claims to have been “actively listening” especially in the regions and the upshot is the draft Regional Energy Transformation Partnerships Framework and draft 2023 Queensland Renewable Energy Zone Roadmap which outline “initial actions and proposed initiatives to support communities”.

While the proof will be in the pudding of the plan’s implementation, stakeholders can be encouraged by the guiding principles which ground the proposed Partnerships Framework.

There is a stated commitment to driving “genuine and ongoing engagement”, sharing “benefits with communities”, expanding “local procurement, manufacturing, and supply chain opportunities”, prioritising “the employment of local people” and skills development, building local capacity and “positively managing changes”, while protecting the environment and empowering the participation of First Nations peoples.

Partnerships with local governments and peak organisations, establishment of reference groups, developing a landholder information toolkit jointly with Queensland Farmers Federation – these are all signs the Queensland Government has learned lessons from the gasfields experience.

Importantly, in the sharing of benefits with the local communities the government has indicated it recognises the importance of industry being able to pool funds to address strategic enabling opportunities and this will be even further enhanced if the government proceeds to match some of the opportunities identified at the regional level.

Reassuringly, while there is still a long way to go, all this means that it is possible for communities, industry and government to learn from past experience and devise better more constructive ways of managing change and building the future.

The essential point though is that if regional development in the new renewable energy zones is to move beyond industry co-existence to real integration economically and socially, it can only be achieved by bottom up initiative and leadership and a system of governance that actually facilitates grass-roots change.

That is the essential challenge facing regional Australia.

[i] Quoted by Sarah Ison in “Climate group warns we’re missing the target”, The Australian 1 December 2023, p4.

[ii] van Assche, K., Valentinov, V. and Verschraegen, G. (2022), “Adaptive governance: learning from what organizations do and managing the role they play”, Kybernetes, Vol. 51 No. 5, pp. 1738-1758. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-11-2020-0759

[iii] See “Adaptive governance: An introduction, and implications for public policy Paper presented at the 51st Annual conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Queenstown NZ, 13-16 February 2007 Steve Hatfield-Dodds, Rohan Nelson and David Cook (CSIRO) sourced at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6418177.pdf

[iv] Queensland Audit Office, Managing Coal Seam Gas Activities Report 12: 2019–20

[v] Gas Industry Social & Environmental Research Alliance, “The Social Licence to Operate and Coal Seam Gas Development Literature Review” Report 31 March 2013

[vi] Queensland Government Media Release, “Locals set to benefit first in new Local Energy Partnerships” Published Wednesday, 18 October, 2023 – sourced https://statements.qld.gov.au/statements/98941

[vi] Queensland Audit Office – Managing coal seam gas activities Report 12: 2019–20

[vii] Brian Towler et al “An overview of the coal seam gas developments in Queensland”, Journal of Natural Gas Science & Engineering 31 (2016) 249-271